Climate finance for emerging countries

Mafalda Duarte, Head of the Climate Investment Funds (CIF), calls for innovative green financial instruments to attract private investment and ‘de- risk’ new infrastructure projects, highlighting Morocco as a shining example.

Twenty-one years is a long time. Long enough to raise a child and send him or her off to college. That’s how long it has taken to get to the Paris Climate Agreement. Climate leaders are meeting this November in Marrakesh to talk about concrete action to implement this historic treaty, and much of that discussion needs to focus on money.

I started off my career more than 15 years ago as a development economist, and for a few years climate change and climatefinance never really crossed my mind. But after years spent on the ground and seeing devastating floods, droughts and the effects of unpredictable weather – particularly in sub-Saharan Africa – I realised how climate change would compromise and potentially roll back the hard-won economic and social progress made by poorer countries, something I care about dearly.

While development economics is my pursuit, these days my life and work revolve around finance. I believe in the key role of innovative and scalable ways to finance climate projects to move us away from an ever-warming planet and its dire consequences.

The signing ceremony of the Paris Agreement was not an unalloyed cause for celebration, because of the dissonance and contradictions observed between the investments and policies taking place worldwide. In particular, there is not yet nearly enough patient and long-term climate finance – whether from public or private sources – to trigger the revolution we need.

We need to realise the urgency, speed and scale of action that is needed and act accordingly. Limiting warming below 1.5°C by 2100 is still feasible, but time is running out. And we need to demonstrate that it makes good business sense for the private sector to step in and step up.

Huge investment needed

Huge investment needed

Research by Bhattacharya, Oppenheim and Stern (2015, http://www.brookings.edu) shows that in the next 15 years, the world will need to invest around US$90 trillion in sustainable infrastructure assets if it strives for a climate smarter world – surely the world we all want to live in and most importantly that we want our children to live in. This includes investment in cities, transport systems, energy systems, water and sanitation, and telecommunications. This $90 trillion of new infrastructure, most of which will be built in developing countries, represents more than the current global stock.

These investments have the potential to bring a lot of benefits but only if they are socially, environmentally and economically sustainable. That means they need to be consistent with a net zero emissions and climate resilient future world. Failure to align the climate action and infrastructure investment agendas could lock-in technologies, planning models and businesses to a high carbon and low resilience pathway for decades to come.

We also know that overall it is more expensive to finance infrastructure projects in developing countries where the needs for renewable energy and other sustainable infrastructure are greatest. Real and perceived risks, including country and political risk, technology risk, and off-taker risk (for power projects) are often too high to attract investors and project developers to invest in climate-smart projects in emerging markets. Investing institutions often feel it is safer to invest money elsewhere, leaving many of these countries without the investment needed to move towards a low-carbon economy.

Concessional financing

Responding to real and perceived risk is where public concessional financing proves its usefulness. Concessional financing is money that is provided at below market-based rates in order to help de-risk the project and attract other investors that would not provide finance otherwise. Concessional financing can therefore unlock climate-smart investments that are deemed too risky for investors, and in some cases, even for development banks. Well-targeted use of this type of financing is necessary to push new technologies, create new markets, and to crowd in private sector financing. Concessional finance is also increasingly necessary to support investments in climate resilience and adaptation, especially in the poorest and most vulnerable countries.

Concessional financing that is ‘blended’ with commercial financing is not an abstract concept, but rather a sound financial strategy that is leading to innovative projects in roof-top solar energy, flood-proof roads and bridges, or reforestation – all of which have real, positive impacts on people’s lives.

For the past six years I have been engaged in the implementation of the Climate Investment Funds (CIF) to support developing and emerging countries make these types of investment choice. I am proud because I see us helping countries like Kenya invest in geothermal energy, while also reducing the costs of electricity to its population. Or India, where an investment of around US$1.2 billion by multilateral financing partners will lead to a serious expansion in rooftop solar energy. Or Mexico, where access to finance empowered local communities in driving sustainable forest management.

Shining examples

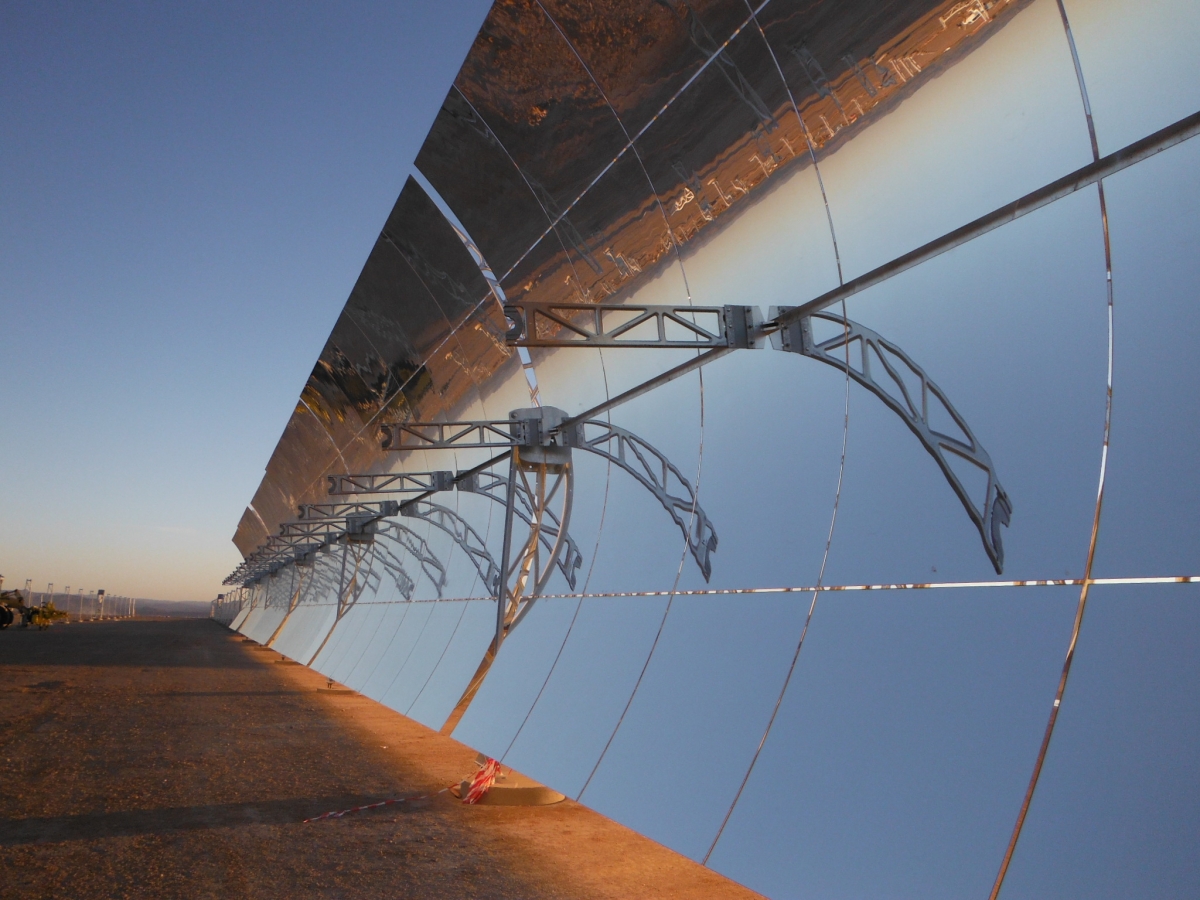

As host country of the 2016 COP, Morocco provides one of the best examples of what concessional financing

paired with other public and private capital and technical partners can accomplish. Last year, the Noor Concentrated Solar Plant (CSP) in Ouarzazate – the largest CSP plant in the world, so big it can be seen from space – was opened. About US$435 million of CIF funds have been invested in the Noor project, which will provide clean energy to 1.1 million households. It is estimated that the plant will achieve over 500 megawatts (MW) installed capacity, reduce Morocco’s energy dependence by about two and a half million tons of oil, while also lowering carbon emissions by 760,000 tons per year.

It provides the foundation for Morocco’s plan to produce two gigawatts of solar power by 2020, equivalent to about 38 per cent of Morocco’s current installed generation capacity. The indirect benefits of the Noor project might even be larger: it has advanced an important and innovative technology, it has driven down costs of CSP, and it holds important lessons for how public and private sectors can work together in the future. It had its own claim to fame when superstar and climate activist Leonardo DiCaprio shared a photo of the plant with his nine million Instagram followers.

Apart from Hollywood glitter, climate finance has truly brought on progress in terms of helping fire off groundbreaking technology and a new market. Concentrated Solar Power is such a promising technology that the International Energy Agency estimates that up to 11 per cent of the world’s electricity generation in 2050 could come from CSP. This is especially relevant for the Middle East and North Africa, a region rich in solar resources.

We need innovative green financial instruments to attract billions of the private capital market; products such as green bonds, climate insurance, and securitisation of assets in climate funds. For example, in Mexico, the Inter-American Development Bank – with the support of the CIF – is implementing a Green Bond Securitisation project. Its objective is to promote sustainable energy investments in small and medium enterprises (SMEs). The Green Bond will provide direct long-term financing to a portfolio of sub-projects investing in sustainable energy initiatives. Our concessional financing will be used for credit enhancement to the portfolio, through the use of a partial risk guarantee to mitigate risks faced, first, by lenders, while the portfolio is developed to reach the critical mass needed for bond issuance; and then by bond investors. Our financing should enable the Green Bond to achieve the credit rating required to attract institutional investors, which would be a first for the sector in Mexico.

Projects like these can convince private and institutional investors that green, climate-smart markets are wide open for business across emerging and developing economies and we – multilateral and concessional financiers – are there to help fertilise it. Concretely, we are planning to do this through the creation of a groundbreaking financing vehicle aimed at offering a unique opportunity for institutional investors looking for a sustainable and diversified portfolio in emerging economies.

Behaviour-changing leadership

Behaviour-changing leadership

Finally and most importantly, we need leadership. We need political leaders to move away from powering our economies with the dirty energy sources we have been using for more than two centuries. We need to make sure we save a lot more energy – which means retrofitting existing buildings and ensuring energy efficiency standards are used in new ones. We need to change behaviours in terms of the way we commute, the way we dispose of waste, the way we consume. And we need to do things dramatically differently in a short period of time.

Yes, ‘Paris’ led to a cornerstone climate agreement, but lots of work is left to be done in Marrakech. They say that “money makes the world go round” – and I hope an honest conversation about finance at COP22 could ensure the wheels of progress turn much more quickly and smoothly.

Read the full Climate Action 2016/17 Publication here